Exploring Identity: How Artists Reflect Personal Identity in Their Work

It’s about 2:15 AM, and the studio feels like the last quiet place on earth. The house is making weird noises, the beer’s gone lukewarm, and graphite dust clings to the side of my hand. I tell myself I’m here to build a habit — two hours of making, no excuses — but many nights, I end up sitting in front of the easel thinking about why I make anything at all.

Trying to decide if I should put out fresh oil paint on the palette or simply work in another, more affordable medium.

The longer I stare at the work, the clearer it becomes: every mark carries a trace of who I am, even the ones I didn’t mean to leave. Maybe that’s what identity in art really is — the evidence of a life lived through the language of making.

When Art Becomes Biography

Artists don’t escape themselves; they translate themselves.

Rembrandt didn’t paint faces so much as he painted truth. His brush revealed the kind of honesty polite society tried to powder over. Monet, haunted by memory and loss, turned light itself into autobiography — time slipping through his fingers. Artemisia Gentileschi poured her survival into myth; Frida Kahlo painted her body like a map of endurance.

Even writers do it. Hemingway wrote like a man hiding behind brevity — each short sentence a trench wall protecting the self. Virginia Woolf let her consciousness blur until thought and identity became inseparable. And Poe, forever haunted by the beauty of decay, turned obsession itself into art — proof that identity isn’t just lived, it’s endured.

They all remind me that identity isn’t decoration; it’s gravity. It pulls everything we make toward what’s real.

The Artist in the Mirror

When I look back at my own work, I can see the story of my life hiding in plain sight.

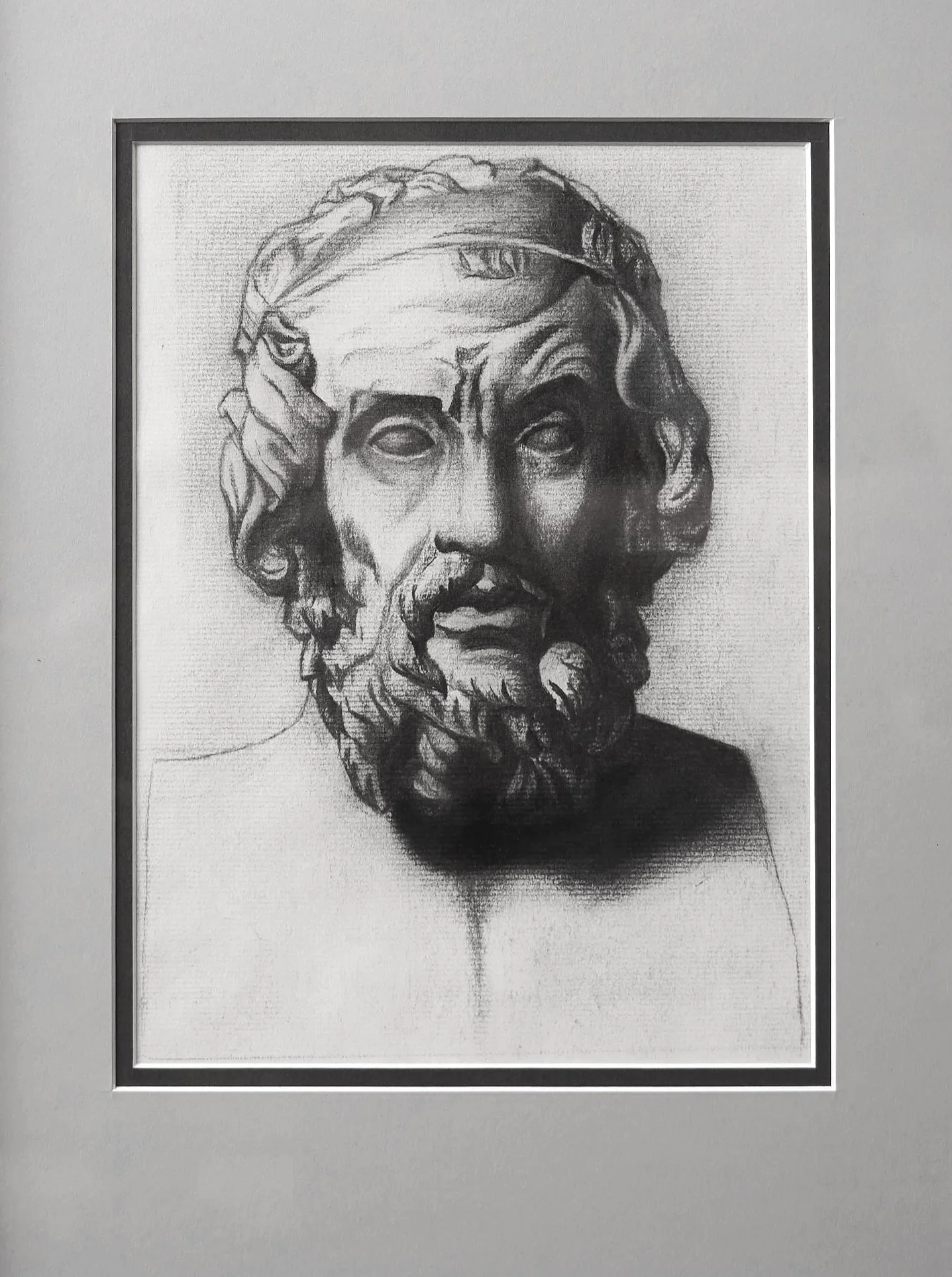

In the charcoal drawing of Homer, I see discipline — that ingrained belief that if something’s worth doing, it’s worth doing right. Every transition of value feels like a small negotiation between perfectionism and patience.

“Homer”

Charcoal on Paper, a study from Bargue Plate I-54

A pen-and-ink drawing of the weathered outbuilding in my backyard brings me home. Those lines are Ohio lines — the rhythm of a small town where nothing seems to come easy, but everything endures. It’s not nostalgia; it’s respect.

My still lifes — bottles, cameras, and cloth — feel like fragments of autobiography. The photographer in me shows up in the composition; the craftsman in the precision; the dreamer in the glow of light hitting glass. Even the objects tell on me: whiskey and wine, patience and reflection, ritual and restraint. I’m in every choice, even when I pretend it’s just about color and form.

The pewter cup and lemons are quieter — maybe the closest I’ve come to painting peace. And the watercolor barn scene? That’s memory turned into place. It’s the world I come from, and somehow the one I still paint toward.

“Life Giving You Lemons”

Oil on Panel

8” x 10”

Are We Living in the Past?

Sometimes I wonder if artists like me are guilty of romanticizing the past. I can’t help thinking of the film Midnight in Paris — that irresistible fantasy that we’d all make truer, deeper art if only we’d been born in another era. (this is one of my favorite movies BTW)

Maybe it’s true that part of me longs for Rembrandt’s candlelight or Sargent’s salon. But when I’m honest, I think what I really miss is certainty — that sense that beauty still mattered and skill was the measure of sincerity.

Maybe nostalgia isn’t an escape; maybe it’s reverence. Every brushstroke we lay down today is a handshake across centuries. I might paint under LED bulbs instead of oil lamps, but I’m still chasing the same thing they were: light, truth, and the proof that something made by hand can outlive the hand that made it.

The A-Team, Cigars, and Influence

Even now, as I write this, the iPad is locked on Netflix, playing the 2010 film The A-Team.

I’ve seen it before, but I love the ridiculousness of it — the impossible plans, the explosions, the grin on Hannibal’s face when he says, “I love it when a plan comes together.” Though I still think George Peppard pulled that line off best.

Something about that line hits me deeper than it should. Maybe it’s because it reminds me of childhood — of Saturday mornings when the world still felt big and full of promise. Or maybe it’s because, in my own way, that’s how I paint. Every work starts as a mission I shouldn’t be able to pull off: the light’s wrong, the form’s tricky, the time too short — and somehow, against the odds, it comes together.

Maybe that’s where my artistic identity really begins — in those small, cinematic victories, born from the same mix of optimism and control that’s always been in me. We are the sum of what we’ve seen and loved. So why wouldn’t a TV show, a smell, a childhood hero, or a single line of dialogue shape how we see and make?

“A Good Stick & Rusty Nail”

Just some random evening on the deck, in the back yard. I was probably thinking about how I’d love to travel the world to make art and share stories.

The influences we carry aren’t just cultural; they’re emotional fingerprints.

What the Work Knows That I Don’t

When a painting is finished, I like to think I’ve said what I meant to say. But later, under different light, I realize the painting knew more about me than I did. The graphite knew I was searching for structure. The ink knew I needed roots. The still life knew I was trying to slow time.

Art becomes the mirror we can’t look away from. It reflects not who we think we are, but who we’ve become in the process of trying. Brush or pen, lens or musical instrument — the tool doesn’t matter. The reflection always belongs to the soul holding it.

Maybe that’s why I keep showing up here at two in the morning...

The tool doesn’t make the art — it reveals the artist.

(Studio self-portrait with camera, 2025.)

It’s not just to make another painting — it’s to meet the person the next one will reveal.

And every once in a while, when the brush lands just right and the plan actually comes together — I can almost hear Hannibal’s line echo through the studio, cigar and all.

Afterword: A Quiet Note

This reflection is part of Letters from the Studio — an ongoing journal about art, craft, and the spaces in between. If it resonates, share it with someone who still believes the work we make carries our fingerprints, long after the paint has dried.